Introduction

Categories:

This white paper presents the profoundly unique, personalized, and adaptable Zen system, under development, for creating web applications—a radically new system usable by a very inclusive class of people. The alpha stage of the Zen project is the building of a small bridge over the gap between codeless, programmerless web authoring and the large-scale web application development that programmers do. There are numerous opportunities to build this small bridge because simple web-page interactions have become part and parcel of a novice’s understanding: copy-paste, URL linking, drag-and-drop, resizing, opening new browser tabs, etc. All such interactions could be created inside a web page via cleverly devised menus and buttons suggesting next steps to the web page visitor. Such interactions are sometimes called wizards and macros, but already that sounds too technical!

A typical example of a web application, aka web app, is a highly interactive website with various kinds of media and interaction. Such a model provides lots of examples of variability between web apps. We all know there are countless websites dedicated to every subject imaginable. So why would anyone but a computer geek want to create one more? Isn’t there already a web app for every need, even for every personal, private need?

Old School

This white paper does not go deeply into the question. Rather, the possibilities will be explored and developed gradually on the website web-call.cc and in the Mashweb Guide. However, the short answer to the question is that a website can best serve an individual if it keeps a laser focus on his particular needs. There are two opposing forces in operation behind website development: the need to conform to the individual web user’s interests and the need to serve a class of people. There are just too many possible requirements for one size to fit all. A few of the infinite possibilities for tailormade websites are presented in this Introduction. This white paper proposes that every literate person should create his or her own web apps.

The web is replacing pen and paper.

In place of reading hardback and paperback books or magazines and journals, and in place of keeping notes on paper, people are reading and writing digital media, especially on the web. There are countless websites dedicated to socializing, employment, cars, sports, self-help, arts, science, religion, and philosophy, millions of subjects large and small, both consequential and inconsequential. The requirements of each website can be as unique as the website’s target audience.

Here is a small sample of the user interactions that can make a website unique:

- searching

- liking

- tagging

- sharing

- posting

- commenting

- chatting

- discussing

- moderating

- uploading

- curating

And that is but a start. The reader might notice that many of these microinteractions are used to turn a website into a social network, but microinteractions like these can define the main utility of any website.

There are also many kinds of specialized media and data a website visitor can interact with:

- short text, like on a microblogging site like Twitter

- long text

- photos

- sounds

- links

- numbers

- interactive graphs

A website can also be specialized by its behind-the-scenes databases and services, that is, by the data it accesses or collects and by its operations on the data.

Someday, Zen might allow any literate person to build their own highly interactive web applications (aka web apps) from scratch and decide virtually every detail of their look, structure, and function simply, efficiently, and quickly without prior learning. This white paper links to live, interactive experiments showing the incremental progress in building Zen. Each investigation tests at least one new function to enable non-programmers to create simple web applications.

But why would anyone but a computer geek want to do that? And why hasn’t someone already made it possible?

The answer to the first question, “Why would everyone want to create web applications?” is that the web is the natural way to organize ideas and information in the digital age. The “Guide to Mashweb” goes into depth about the problems people of the Digital Age encounter every day, but the main advantages of the web over other forms of electronic media are:

- the web is everywhere on our planet,

- the web enables hypermedia, i.e. web links,

- the web encompasses multimedia, and

- the web, through HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, gives structure to data, i.e. ways to organize data.

The answer to the second question, “Why hasn’t someone already made it possible?” has two parts. First, the “group think” among programmers is so strong that no one has noticed the relevance of a little-studied capability of a little-studied programming language. This capability can shrink the programming task an order of magnitude and encourage the exploration of ambitious new paradigms of the user interface. Second, the new paradigms will enable Zen to work inside documents to build organized media rather than outside as a “bolted on” application. Working inside web pages will make Zen natural and powerful. The current “Zen White Paper” goes into depth on the subject of Zen’s key technologies.

Zen’s unique selling point (USP) will be in-context, instant feedback, full-featured editing of website or web application structure, function, and styling. Zen will make it easy for users to create valid HTML and styles in web pages without getting into the complexity or distraction of code. Zen users will quickly develop basic web application programs using visual-programming principles adopted from successful visual-programming languages for children. Most importantly, all this “development” and its deployment can be continuous, carried on by a website’s users of all levels of experience. Deploying and sharing a new application could be as simple as clicking a Share button. Self-organizing Zen user communities might even develop novel applications.

The unusual part of Zen will be free software that programmers can use to give their websites Zen’s unique capabilities. Zen’s core (“Core Zen”)1 will work with virtually any website’s server technology. Model website server technology2 will develop alongside Core Zen. It will be made available on the internet,3 providing user registration and private accounts for users who want to save their work.

The book No Code Required4 describes many user-programmed systems for customizing websites but none for creating web apps. Zen will enable the easy creation of many kinds of web apps. Children write application programs in specially designed visual programming languages, so why not adults?

Many problems of end-user programming environments for the web have been overcome to some degree or other by the thousands or millions of web developers in the world. However, the biggest of these problems arises from the stateless nature of the web. To illustrate, let us first review how simple and straightforward it is for a typical desktop program to ask a user’s name and greet him accordingly:

PRINT "What is your name?"

INPUT "(Enter your name.)", $name

PRINT

PRINT "Hello, "; $name; ", how are you today?"

The flow of this program is apparent but can only work on a platform that hides complexity. It must be halted, waiting for a response. For desktop applications, the operating system provides system calls, a scheduler, and library functions that allow the look of such a program to mirror its progress. There is no underlying operating system for web applications to support the halting and restarting of the program. However, the Scheme programming language supports first-class continuations.5 , 6 , 7 , 8 These continuations allow programs to be halted and restarted using language-level mechanisms (as opposed to operating-system system calls and library functions). Zen will utilize continuations to simplify both the Zen developer’s job and the user’s programming tasks.

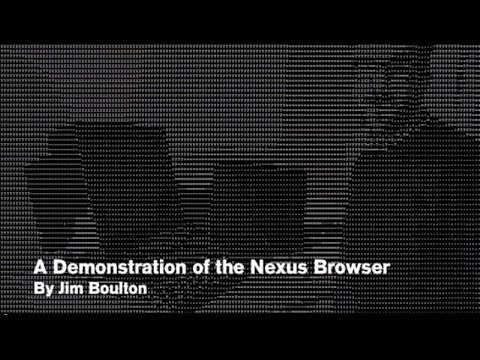

This paper will explain the appeal of Zen’s new approach and the plan to make work it work. A brief video from the Digital Archaeology project9 showing the operation of the first web browser can provide some background context. The video shows the function of the first web browser, called Nexus, crafted by the inventor of the World Wide Web himself, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. Nexus’s editing function is demonstrated twelve minutes and nine seconds into the video (Figure 1). Thus, Berners-Lee intended the web browser to enable easy collaborative authoring from the very beginning. However, as he says, “It didn’t really take off that way.” 10 , 11 , 12

Figure 1. Demonstration of the editing function of the first web browser. Click to open.

Now, a quarter of a century later, the position of the A-grade web browsers13 , 14 , 15 , 16 as the central applications for online sharing seems unshakeable. Yet till today, not one A-grade web browser has full-fledged web-authoring capabilities. (We shall discuss the browser features contentEditable and designMode later, since these do not, without external programming, constitute web-authoring capabilities.) The direct descendents of Berners-Lee’s early web-page editing application are visual web-page editors in three classes:

- the class of rich-text editor that is embedded right into a web page. (Programmers might like to know that these are WYSIWYG web-page editors that convert HTML

textareafields or other HTML elements into editor instances.) TinyMCE and CKeditor are typical examples. - the class of standalone WYSIWYG web-page editor that operates on web-page sources and shows a preview of the resultant web page. Sources can be HTML or markup to be translated into HTML.

- the class of WYSIWYM semantic web-page editor. Examples of this type of editor are WYMEditor, RDFaCE, BlueprintUI, PageDown, and Showdown. (The author needs to further investigate these editors.) Source can be HTML or markup that can be translated into HTML.

Apart from editors that only edit web pages, there are other tools and applications for developing web experiences:

- online web development tools for testing and debugging code (e.g. JSFiddle.net, CodePen.io, jsbin.com, etc.),

- web-developer tools and “augmented-browsing software"17 , 18 , 19 , 20 (e.g. Firebug for Firefox, Developer Tools for Chrome, Developer Tools for Safari, Greasemonkey, Tampermonkey, Chickenfoot, X-Ray Goggles),

- integrated development environments (IDEs) that build websites,

- web content management systems (web CMSs or simply WCMSs),

- website builders,

- web frameworks, and

- web portals.

Feedback

Was this page helpful?

Glad to hear it! Please tell us how we can improve.

Sorry to hear that. Please tell us how we can improve.